You are here

Life and loss at sea: shipowners and the seafarers they abandoned | Context by TRF

Life and loss at sea: shipowners and the seafarers they abandoned | Context by TRF

Katie McQue 20 October 2025 https://www.context.news/money-power-people/long-read/life-and-loss-at-s...

What’s the context?

When a seafarer lost his leg in an accident, his employer left him on his own in one of the growing cases of ship abandonments.

Rakesh Padmamurti was working in the engine room of the cargo vessel SL Star while it was docked at a port in Iran.

As a crane loaded it with heavy cargo, the ship suddenly lurched to one side, sending its frightened crew rushing for shore.

Before Padmamurti could follow his 10 colleagues to safety, the gangway flipped and the ship capsized, trapping him underneath.

“I went completely underwater, and my leg was separated from my body,” said Padmamurti, who was 23 at the time of the incident in 2019.

His leg was severed in half by the rolling ship, but this freed him. He swam to the surface and grabbed a life jacket someone had thrown into the water.

Stunned and bleeding, Padmamurti fought to stay conscious as his colleagues begged workers at the Shahid Rajaee Port to help. He was eventually driven to a nearby hospital in the city of Bandar Abbas, accompanied by a fellow Indian seafarer named Aftab Alam, and underwent emergency surgery.

His leg below the knee was gone.

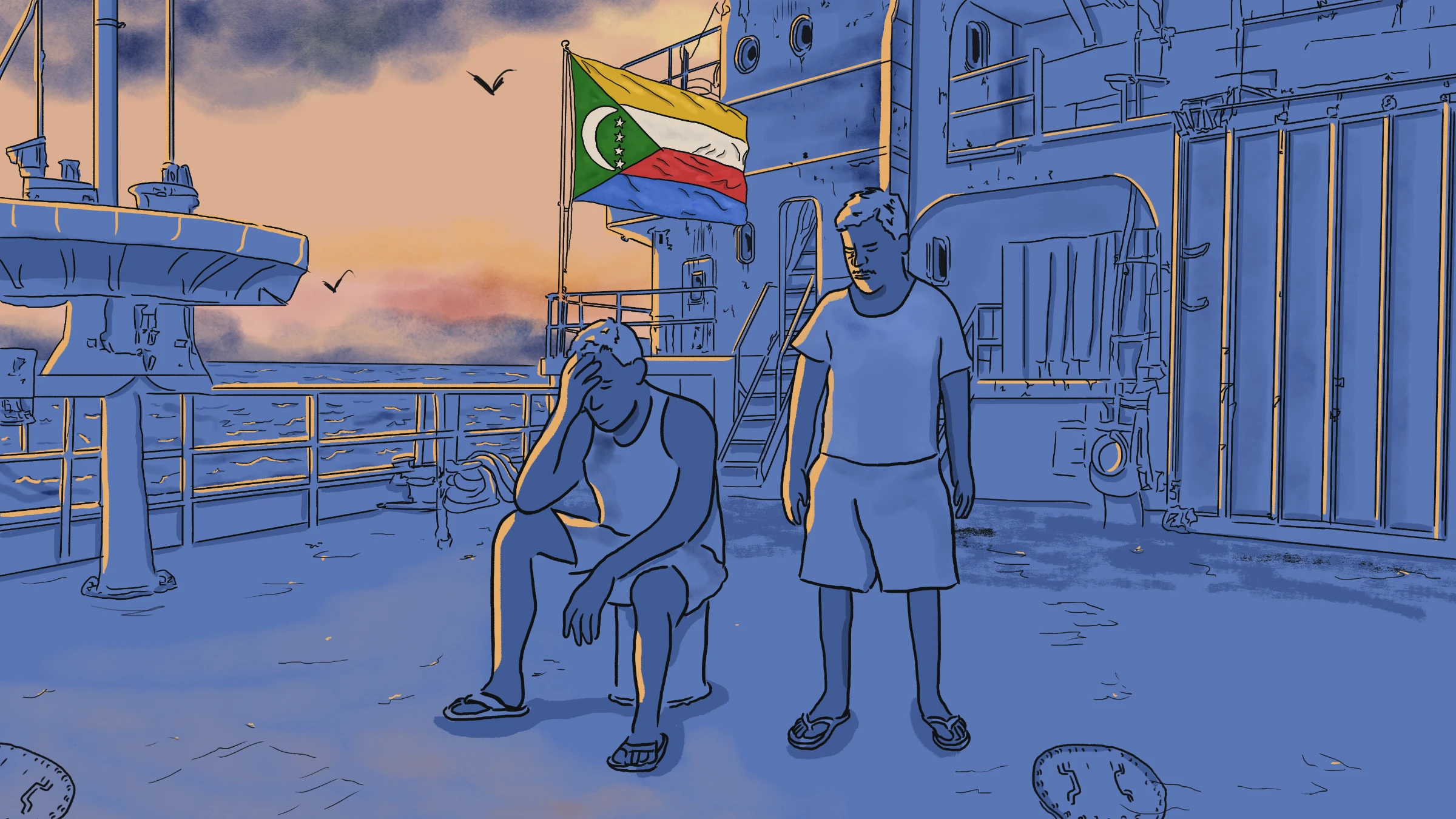

Padmamurti and Alam stand on the deck of the SL Star at sea. They were employed as seafarers in Bandar Abbas in Iran. Padamurti was 23 and Alam 21 at the time of the incident. Alam is still owed $2,450 in unpaid wages from his time in Iran. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Padmamurti and Alam stand on the deck of the SL Star at sea. They were employed as seafarers in Bandar Abbas in Iran. Padamurti was 23 and Alam 21 at the time of the incident. Alam is still owed $2,450 in unpaid wages from his time in Iran. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

No one from the shipping company offered any help or support, Padmamurti said.

Alam, who was 21, volunteered to nurse Padmamurti over the next two months, helping to bathe him, use the bathroom and keep his spirits up.

Far from home, the two young seafarers had no money, no passports and no change of clothes. Alam slept on the hard floor next to the hospital bed. The hospital did not provide food to non-patients, so he ate leftovers from patients’ plates.

Weeks dragged on as Alam messaged the ship owner, a Dubai-based firm called Sea Link Shipping, to plead for assistance. But there was no response.

They had been abandoned.

Sea Link Shipping did not respond to requests for comment.

Padmamurti and Alam are among the thousands of seafarers deserted by their employers in recent years, often left without pay, medical help, food or a way home as a growing number of ship owners abandon vessels to avoid legal troubles, debts or costly maintenance.

Cases of seafarer abandonment surged to a record high of 3,133 seafarers in 2024, up 187% compared with 1,676 in 2023, according to data from the International Transport Federation (ITF), a global authority on transport workers’ rights and welfare.

Unreported cases likely push these numbers much higher, experts said.

The rise in seafarer abandonments is driven by growing financial pressures on ship owners, including volatile freight rates, the high cost of operations and the expense of ship maintenance, the ITF said.

Seafarers growing more willing to reporting their abandonments have also contributed to the rise in numbers.

Like Padmamurti and Alam, the majority of abandoned seafarers are Indian, according to the ITF.

Indian nationals comprise about 10% of seafarers worldwide, and trade links between India and Iran in particular have facilitated a supply of Indian seafarers looking to the Middle Eastern nation for work.

Usually trapped on board vessels in gruelling conditions, stranded seafarers may endure extreme hardship with little hope of relief for months and sometimes years.

A lack of enforcement of international maritime rules is among the factors allowing this practice to proliferate.

Every vessel must sail under the flag of the nation where it is registered, subject to that country's laws while at sea. But minimal oversight by some flag states and port authorities means there is little accountability in the industry.

An absence of vessel insurance, the slow resolution of legal disputes and ship owners’ refusal to meet their responsibilities to crew members have left victims fighting for their basic rights in an industry that frequently turns a blind eye on its worst operators.

These seafarers cannot sail away or escape the vessels due to a lack of fuel, intimidation or because they are compelled to keep operating the ship if they are to have any hope of receiving unpaid salaries.

A seafarer holds an Indian passport. Indian nationals like Padmamurti and Alam comprise about 10% of seafarers worldwide. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

A seafarer holds an Indian passport. Indian nationals like Padmamurti and Alam comprise about 10% of seafarers worldwide. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Port authorities can also be complicit in an abandonment by failing to provide assistance to the crew or by confiscating their passports to ensure they will not leave the vessel unmanned, said Steve Trowsdale, inspectorate coordinator at the ITF.

The scale of the problem has overwhelmed Trowsdale’s team which works in ports to enforce seafarers’ rights, investigate complaints, recover unpaid wages and intervene in cases of abandonment or poor working conditions.

“The seafarers are frightened into not saying anything. We have 135 inspectors, and they are full-time dealing with this stuff,” he said.

Rising operational costs in the Middle East and the growing number of small ship management firms that exploit regulatory loopholes to cut costs are also driving the surge in seafarer and vessel abandonments, experts say.

Some ship owners abandon vessels when they fail to secure new business, especially when the maintenance for dilapidated ships is costly, according to Chris Partridge, managing director of the consultancy Myrcator Marine & Cargo Solutions.

These cost-cutting tactics come at a steep human price.

Young men seeking to launch maritime careers are especially vulnerable, and many take jobs with less reputable shipping companies in the hopes of gaining experience at sea.

“Maximising profits in a quick way can only happen with severe exploitation. This should worry the industry as a whole,” said Mohamed Arrachedi, ITF’s network coordinator for the Arab World & Iran.

“These people create unfair competition with the good ship owners. Why are there no serious attempts to eradicate this?”

At the hospital in Bandar Abbas, Alam tried to shield Padmamurti from the reality that they were alone in Iran with no one to turn to for help.

He frantically emailed his Indian recruitment agency, the vessel’s state flag of Comoros, the Port and Maritime Organisation of Iran and the ITF.

For weeks Alam heard nothing. The ship’s captain had returned home to Pakistan. The rest of the Indian crew was staying at the port’s guesthouse, also seeking help to repatriate and get paid the salaries owed to them.

Eventually, the ITF and a representative from the insurance company visited the men in the hospital and offered to help them repatriate.

“But they say, ‘Go back to India, we will fight for you, and we will get you your salary,'” said Alam, adding that he knew if they left Iran they would never get paid.

A map shows the route of the SL Star's eight-hour journey back and forth from Bandar Abbas, across the Strait of Hormuz, to Jebel Ali port in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, transporting construction materials. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

A map shows the route of the SL Star's eight-hour journey back and forth from Bandar Abbas, across the Strait of Hormuz, to Jebel Ali port in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, transporting construction materials. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Alam is still owed $2,450 in unpaid wages from his time in Iran.

The Indian recruitment agency and Port and Maritime Organisation of Iran did not provide comments to Context on the situation.

“The reason why it's so much more difficult to still be paid if they go home is once you leave the ship, you have no lien over the ship,” said Partridge.

Returning home with no salary can be devastating, since many seafarers and their families have taken hefty loans to pay the recruitment fees necessary to get their jobs, said Chirag Bahri, a New Delhi-based director of International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN), a non-profit that assists maritime workers in distress.

Bahri, a former seafarer, was held hostage by Somali pirates for eight months in 2010. Since then, he has worked to provide support to seafarers in distress.

“Even $1 is extremely important for them. And after seeing that they have lost thousands in all of this process, it's a big shock for them,” he said.

As the seafarers wait in the hopes of getting paid their salaries, their mental health often deteriorates, he added.

Young seafarers frequently have been tricked or pressured into paying recruitment fees that can run into the thousands of dollars.

Many take out high-interest loans or their families sell off assets, plunging them into financial entrapment, experts say.

This practice, known as debt bondage, is a red flag for forced labour, according to the United Nations’ International Labour Organization.

Unprincipled ship owners take advantage of the seafarers' desperate plight, said Partridge.

“The ship owners rely on the fact they're going to give up,” he said. “They force them into submission. They don’t give them food, water, they don't have fuel, so they'll just want to go home.”

Padmamurti had dreamt of a life at sea since childhood after spending time on the fishing boat of a family friend.

He applied to the Indian Navy but was rejected four times, so he decided to pursue a seafaring career in the private sector instead. He took training courses and acquired the qualifications needed for a job on board a merchant ship.

His journey led him to Mumbai, India’s bustling hub for maritime jobs.

Padmamurti fishes on a boat at sunset. After spending his time on the fishing boat of a family friend in his childhood, Padmamurti had always dreamt of a life on sea. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Padmamurti fishes on a boat at sunset. After spending his time on the fishing boat of a family friend in his childhood, Padmamurti had always dreamt of a life on sea. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Competition is high among first-timers who hope to gain critical experience. They know their first job may be tough, underpaid and possibly dangerous, yet take the risk.

For months, Padmamurti knocked on the doors of shipping companies and recruitment offices, looking for work while taking part-time jobs.

One day, a recruiter offered him a job at sea with a staffing agency named Frontline Ship Management Pvt. Ltd, paying $250 a month.

But there was a catch - Padmamurti would have to pay $2,000 upfront.

“I was shocked, but my main focus was on gaining experience," Padmamurti said.

Frontline, which is no longer in operation, did not respond to requests for comment.

Mulling it over with his family for two weeks, Padmamurti decided to pay the fee and took out a bank loan.

The interest on the loan was high, and he only finished paying it off in October 2024, after he had been home more than four years.

Heading out for his first seafaring job as an electrical officer, Padmamurti recalls being excited as he flew to Mumbai, to Dubai, to Tehran and then to Bandar Abbas.

When the SL Star set sail, the Indian crew, most of them rookies like Padmamurti, celebrated. The ship’s cook prepared them kesari bath, an Indian dessert.

Kesari bath, or saffron rice, an Indian dessert is prepared by the cook of the SL star for the crew to celebrate the ship setting sail. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Kesari bath, or saffron rice, an Indian dessert is prepared by the cook of the SL star for the crew to celebrate the ship setting sail. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

The next few months were spent making the eight-hour journey back and forth from Bandar Abbas, across the Strait of Hormuz, to Jebel Ali port in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, transporting construction materials, including marble tile.

The work was tough with long hours and the crew grew uneasy as time passed and wages never arrived.

Padmamurti and Alam were among the nearly two million seafarers employed in the maritime industry, the lifeblood of the global economy with the trade of goods, energy supplies and food reliant on a vast network of some 60,000 merchant ships constantly sailing the oceans.

The global cargo shipping market was valued at $2.2 trillion in 2021 and is projected to reach $4.2 trillion by 2031. About 90% of the volume of international trade in goods is transported by sea.

For ship owners, the business can be tumultuous and profit margins can be tight, said Partridge, citing fluctuations in demand, fuel costs and geopolitical tensions.

"Some companies can’t get cargo contracts because the ship is too old, or the ship is in poor condition and they can’t afford to repair it," said Partridge.

"They’ve been ripped off by management companies."

"There’s an awful lot of hidden costs in shipping.”

Other companies operate in the shadow of the black market, where work, out of reach of laws and regulations, is especially perilous, experts said.

“These owners already operate outside the law, so they can do whatever they want with you,” a maritime expert warned.

“They’re unlikely to pay fairly, they ignore safety regulations and when disaster strikes, there’s no insurance or support to fall back on.”

Six years have passed since the SL Star vessel capsized in Iran, a disaster that cost Padmamurti not only his leg but his livelihood.

The pair eventually got home after getting a small sum of money from the ship’s insurance company to cover the cost of their flights back to India, said Alam.

But none of the seafarers working on the SL Star ever received a penny of the salaries they were owed.

Today, Padmamurti lives in the small town of Chilakalamarri, Andhra Pradesh, with his uncle and younger brother. His parents recently died.

Despite mastering the use of a prosthetic leg, he finds steady work elusive. He struggles to make ends meet with occasional agricultural jobs.

The accident on the SL Star has been blamed on negligence by the crane operator who misplaced the cargo on the deck.

"If the ship owner and employer had taken appropriate precautions, the incident could have been prevented," Padmamurti said.

"This incident completely changed my life, altering all my plans and goals."

He said he had hoped for a seafarer position to support his family but now feels guilty that he had joined the ship against his family’s wishes.

"I had to convince them," he said.

He remains close to Alam, who has had a successful career as a seafarer on cruise ships for a major company travelling to ports in the United States and Europe.

Alam stands alone at the head of the ship. Today, Alam has had a successful career as a seafarer on cruise ships for a major company travelling to ports in the United States and Europe. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Alam stands alone at the head of the ship. Today, Alam has had a successful career as a seafarer on cruise ships for a major company travelling to ports in the United States and Europe. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

But the trauma from his time in Iran remains, and he cannot forget his mother’s cries when he told her about his abandonment.

"I was the only one in my family to earn money for seven people. I felt like a loser," he said.

Alam said he tries to send money to Padmamurti when he can afford to do so.

"I am settled in life but he lost his leg. His parents died,” he said. “No one is there to take care of him."

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Ocean Reporting Network.

Reporting: Katie McQue